The apocryphal and the archival appear as the twain that seldom meets. This truism is particularly aggravated in India where archival preservation is a remote possibility, much less a responsibility borne by the state. Consider then the fate of UP politics, which has long been relegated to both neglect and amnesia in popular memory despite the state’s outsized contribution in the tenor of national affairs and the political fates of those who wish to stay comfortably in Delhi. Apocrypha, or oral history, then assumes the important position of preserving by word of mouth, histories that would otherwise only survive the average human lifespan. For those of us interested in Charan Singh’s life, the archives only represent a fraction of his work and influence — and for someone barely remembered in the media and academia beyond epithets of “agrarian/rural/Jat leader” our work to preserve these histories becomes all the more urgent. In pursuance of this belief, we paid a visit to some of Charan Singh’s old associates in Lucknow.

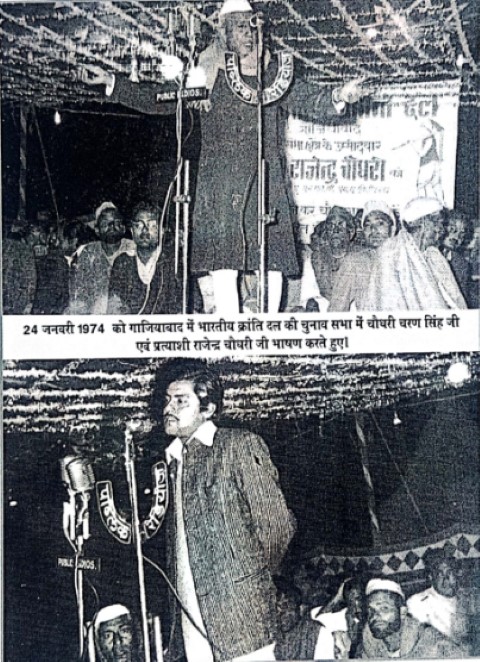

Election rally in Ghaziabad for the 1974 election. Rajendra Chaudhary seen delivering a speech with Chaudhary Charan Singh

From Ghaziabad to Lucknow is a long journey, one typical of the political ascent it exemplifies — the train takes one through ravines and rivers and hundreds of kilometers of farmland. For a journey that takes one to the roiling center of power in the state, the landscape serves as an ironic reminder of the people and the hundreds of millions of lives and livelihoods at stake. This area has recently been the hotbed of protests that have continued ceaselessly since 2021 in large and small scale to effect a legally guaranteed Minimum Support Price for farmer crops and the implementation of the now-famous Swaminathan report, pensions for farmers, debt waivers among others demands of a mostly forgotten rural world. Populated by a series of agrarian households with increasingly smaller landholdings owing to dispossession by debt and generational division of lands, the average landholding size for a family is a pitiful 0.8 hectares as per 2012 figures. [1] Agrarian income has had to be significantly supplemented with service-based wages and livestock for the households to keep their heads above water. Non-payment of dues to sugarcane farmers by mills is a perennial problem, [2] there is little insurance against frequent crop-failures — Uttar Pradesh alone saw a 42.13% increase in farmer suicides in 2022 from the preceding year. [3] Peasant distress has become the background hum of life in UP, and it’s always a surprise revelation that the peasantry doesn’t rise in revolt. The tranquility of an early morning journey conceals much, but these tensions lay at the heart of our inquiries and Charan Singh’s life. What we have today isn’t the future he would’ve envisioned for India.

Lucknow, like every centre of political and administrative power, feels like it rests upon marshland — not quite stable and endlessly shifting. The view of the city from autorickshaws we scuttled through from appointment to appointment revealed the usual dramatis personnae and mise-en-scene expected of it — more policemen than people, party workers donning a motley of insignia, party flags, hoardings full of claims and counter-claims and recherché yesteryear colonial buildings reconverted to portray more decolonized trappings: a bespoke statue of Charan Singh also welcomed us at the steps of the UP state legislative assembly. It is an imposing world foreclosed to the hoi-polloi, easily distinguishable from its khadi and white kurta-pyjama clad power wielders, and is instantly intimidating to anyone new. I count the number of women I see on my fingers. The mass character of the city is overwhelmingly male.

Charan Singh first made his way to Lucknow in 1937 as an MLA from his native heath of Meerut after being appointed as a parliamentary secretary (junior minister). He served on this post till 1950, thereafter taking on multiple portfolios as a cabinet-level minister in every subsequent Congress government till 1967.

Bossism and corruption had disordered the once thriving intellectual environment of the Congress, with the now-familiar post-colonial scene of the local (almost entirely higher Hindu caste) elite scrambling to fill the positions vacated by the departing British colonialists to gain power and pelf. By the 60s the party little resembled the force of the nationalist movement it had once been, a fact Charan Singh often spoke of with a deep sense of despair. He spent years being denied what he considered his political due, and being handed toothless portfolios by average caliber Chief Ministers after Govind Ballabh Pant where he was straitjacketed to effect any real policy change. The 1967 elections – with the colossus Nehru gone from the scene and Indira Gandhi not yet the force she was to become - afforded him an opportunity to break loose from the festering swamp of petty minded, increasingly corrupt and factional individuals that was the rump of the Congress. He left the Congress with 17 MLAs after the election in which the Congress and opposition came out evenly matched, formed the Rashtriya Jan Congress and was elected the Chief Minister of the Sanyukt Vidhayak Dal on April 3, 1967 thwarting his Congress political rival C.B. Gupta’s attempt to rake the seat.

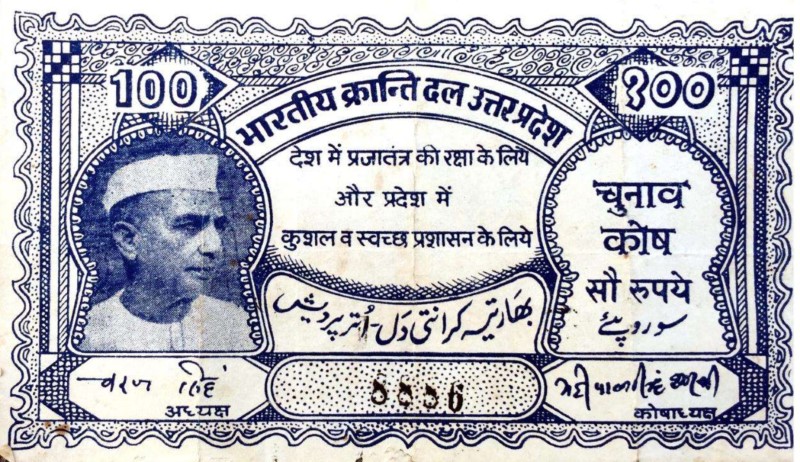

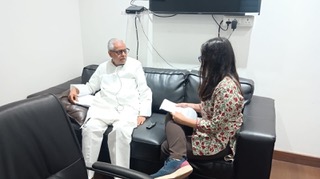

In the same year, non-Congress ministers across India came together to form the Bhartiya Kranti Dal which later consolidated under Singh and become a Hindi-belt dominated party. Rajendra Chaudhry, the currently serving spokesperson of the UP Samajwadi Party, was one of the many youthful politicians who was catapulted into corridors of power by Charan Singh’s discerning eye. We had the opportunity of sitting down with him for an interview, and he recalls his surprise at being offered a ticket from Ghaziabad in the 1974 elections — he was pursuing his LLB from Meerut University when he first met Singh as the chairman of the Student Union. Singh was notably against the existence of student unions in UP, and felt students should prioritise their education over politics. This did not prevent him from separating the wheat from the chaff in student politics as it were; he assured Rajendra Chaudhary that he has a future in politics and must accept the ticket from Ghaziabad in the forthcoming elections. Chaudhary noted his apprehensions — still being a student and not having money — but Singh was undeterred and implacable. In typical BKD fashion, the funds for the campaign were donated by the people. The love for Singh was such that Chaudhary had money to spare after the election cycle ended. A similar tale is relayed to us by Shivkaran Singh of the RLD who was initially a part of Singh’s security detail for a rally and an ex-army man. UP political stalwart Beni Prasad Verma arrived late for the procession he was overseeing, and he refused to let him on the stage lest the rally be disturbed. Always having a keen eye for political temerity and incorruptibility, Charan Singh was immediately impressed and asked him to consider a career in politics. While his initial foray was through the Congress party, Shivkaran Singh is now the Rashtriya Sachiv of the Rashtriya Lok Dal, which he considers a fated homecoming.

The current landscape of UP politics and politicians would not be recognisable without Charan Singh’s many interventions over decades. Most of the leaders he brought to center political stage are now dead and gone, and the few that are left are distributed among myriad political organisations, many at odds with each other, yet the warmth of their remembrance appears the same.

“ईमानदारी” or honesty was the most common refrain in people’s memory of him. He left a lasting impression as an incorruptible politician and would value only those who followed this policy with firm fidelity. Shivkaran Singh remembers his dismissal of all patwaris immediately upon coming to power, among whom corruption had become rife for decades, as an outstanding political achievement in UP politics. Since this position was ritualistically given only to a single (high) caste, he was further incensed against them. [4] His parties too would run on dimes donated by the people based on their faith in the man. He relinquished all material means, Rajendra Chaudhary tells us, didn’t buy himself a single plot of land and made it a point to never hold concert with industrialists. Even after serving as Prime Minister, he did not have a car. When he made inquiries about buying one, the only question he had was how much petrol it could consume. Eschewing the typical Ambassador, which is a mainstay among Indian politicians, he bought himself a Fiat on three instalments with party funds — citing it as the more ergonomic choice.

He had no trepidations about dismissing candidates should there be any blot on their character. During one of these rallies, Shivkaran Singh tells us, he was told by locals that the man he had chosen was corrupt. Without thinking twice, on the electoral campaign stage, he declared that he had made a mistake and people should not vote for his party. Such an approach of putting human character first seems impossible in our times.

His sense of justice was resolute. Upon hearing of payment delays to farmers for sugarcane, a problem that abides today on a large scale, he instructed the local DGP to lock and seize factories if arrears were not cleared in 15 days. The cold remove at which he kept mill-owners afforded him the ability to achieve something contemporary politicians would find difficult to consider given their patronage networks.

These instances instilled an unshakable trust among the people. Remembering his rallies, Rajendra Chaudhary recalls the crowds that would accumulate after one call — during the boat club rallies he saw people from Bengal, Rajasthan, Haryana and Punjab arriving in Delhi through whatever means possible. Many had walked hundreds of kilometres to listen to him. Even out of complete earshot they sat occupying many miles outside the venue. He gave the farmer a sense of propriety in the nation’s capital and in its decision making, and despite its sizeable agrarian population, this was a novelty in Indian politics.

Village, worker, farmer and the poor were the foundations of his politics. Allusions to his caste background were like abuses hurled at him, Rajendra Chaudhary reminisces — “I speak of agrarian matters and farmers,” he would say, “yet these people only call me a Jaat leader” — the hallowed halls of Delhi journalism continued to paint him with a broad brush instead of taking his politics seriously. Chaudhary also firmly believes that characterisations of “kulak” and “communal” were only used to dismiss him and his achievements — he considered peasants to be a unified unit, as the Zamindari Abolition Act he’d helped draft and shepherd through the UP legislature in 1952 had removed class distinctions among peasants. Further ceiling legislations had dispelled whatever class fetters persisted, and thereupon he based his politics on a singular peasantry — regardless of and beyond both caste and religion, the two identities most Indians align with. Muslims voted for him in throngs despite his Arya Samaj background because of the honest and pro-farmer policies he supported and the personal image of incorruptibility and morality he evinced. His public meetings addressed issues of production, acreage and other practical issues that plagued farming communities and he never once made dog whistles to communalism and casteism. Distressed farmers would often come to Lucknow and Delhi when he was in political power and easily secure an audience with him. It was the peasants who had thrust the mantle of power in his hands, and he remained their leader in both thought and action. His political disagreements with the Congress (and indeed all political parties) rested on the same bedrock — a meager allocation of national resources to agrarian India for livelihoods and citizen services and the strain of venality that had become a tumor in the party. Given his independent charge, he transformed party politics from an aloof urban entity to an ubiquitously rural one.

Rajendra Chaudhary’s parting words to us are echt BKD politician: “those for whom politics is freedom, and for whom freedom has been won, don’t have power in their hands. They are only voters. How power reaches the masses was a matter of concern for him.” Parties treat the “voter” as a statistical quotient within which all human aspirations and hopes are sublimated and finally subsumed. Gathering votes is the ultimate raison of politics. What remains are numbers and seat divisions and little concern for the pandemonium that trails the common man in this country. Charan Singh even then rang alarm bells in the Congress on the lack of political and administrative representation of farmers’ sons and backward communities. His political conflicts within the Janata Party from1977 were not solely about capturing seats and retaining power — his record shows the steadfastness with which he resigned from positions once he knew couldn’t effect change — but about policies being that were being without prioritising the masses of the country, particularly its farmers, the rural landless and urban poor. The mythos of him as a power-hungry politician are thus laid bare.

These oral accounts hence give us a fuller sense of the man. Him and his followers remind one of a different era of this country that has long gone. The likes of Charan Singh, Rajendra Chaudhry and Shivkaran Singh are products of a time that allowed farmer’s sons to socially ascend from their villages to seats of power in Lucknow and Delhi. I spent two days among them. This limited time separated me from contemporary politics and put me in a world of simple men, with simple goals, pursing simple politics. This is the gift of remembrance.

Charan Singh paid his dues to the people who made him what he was, gave the peasant self-confidence and security in his land, took from zamindars and the wealthy eddies of social privilege and tried to distribute it among those who were told they couldn’t ever have it. It is now nearly forty years since the rough-hewn, dhoti-kurta and Gandhi cap-donning Charan Singh left us. All the lives he touched continue to carry the torch of his cause and memory.

To us, the act of recording and archiving then becomes radical — to never extinguish his thought, his name, and the belief he inspires among those who toil on the lands that feed us and those small landless artisans who make everything else that once greased the wheels of our rural economies.

Sources and References

.[1] https://oar.icrisat.org/6255/1/AERR_25_1_25-35-2012.pdf

.[2] https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/meerut/up-sugar-mills-owe-cane-farmers-over-rs-9000-crore/articleshow/97845813.cms

.[3] https://rrjournals.com/index.php/rrijm/article/view/1095

.[4] For more on this: https://charansingh.org/archives/leadership-and-power-honour-corrupt-system