Minerva’s owl only takes flight at dusk. History, critical reflection, arrive at the scene only too late — the din and tumult of the times have to pass for them to deliver judgement. To those with the luxury of retrospection, this moment is a cause for celebration. The dust has now settled on the events of the 20th century, though its subterranean effects on the vast majority of the nation’s public still abide. The misgivings of the politics then baptised the country with a fate that has kept us locked in time, ossified in social formations and vertical hierarchies that shouldn’t have survived the end of colonialism.

History comes late, and the legacies of its cast of characters appear burdened with hopes, expectations and inevitably with nostalgia and chicanery. This is no place to repeat platitudes, but which histories are told and which ones neglected come to light while perusing academic work on the politics of Uttar Pradesh. Certain august figures and Big Events entirely eclipse the currents of politics that were coursing through rural India; energising and reconfiguring what politics was meant to be. So we arrive with history, armed with an urgent motive, to uncover the archive of Charan Singh’s political involvements after his many decades of commitment to the Indian National Congress. These years are integral to the man’s own development as a political colossus, but also in the change they bring about in national and state politics.

1967 saw the curtain raised on a new era of anti-Congressism. Erstwhile members of the party in the 60s took steps to challenge its corruption and moral degradation, lust for power and disorder, and issued the party its first organised and forthright challenge. There are no complete works on the Jan Congress led by Charan Singh, nor much ink shed on its organisational structure, leadership and the breadth of its vision. The following is an attempt to introduce the party(s) and its social and economic milieu, along with the changes it went through the course of the 70s. While historiographical accounts have largely skipped over the phase that intervenes between Charan Singh’s time in the Congress and the BKD, our archival research suggests a complex picture: his short-lived Jan Congress in 1967 cannot be ignored within the larger history of his political own development and that of his ideas.

To Charan Singh, three decades of independence had been enough to render it a pyrrhic victory. In an interview given in February 1967, he admitted that corruption and disorder had become so endemic that it seemed impossible to ever rid ourselves of it. “The West and its beguiling riches have unmoored us from what we were. Everyone wants to accumulate wealth. Tell me, how will we survive with our roots torn off?” [1] He mused.

This scale of corruption wasn’t going to escape the public’s eye. The Congress’ waning influence after Nehru was reflected in its electoral performance in the Uttar Pradesh state legislature elections of 1967 where they managed their lowest tally ever – only winning 198 of a total 423 seats and losing their majority. The balance had palpably shifted for the first time in the state’s history, and Congress seemed like it was trudging towards oblivion. C.B. Gupta, Singh’s long-time adversary and petulant representative of the party’s old guard, won his own seat in the legislature by a narrow margin of 72 votes. [2]

The antecedents of this “rivalry” are well worth discussing. For this we must pull focus: the end of Pant’s regime in the state had thrown older power blocs into a flux. Singh was a loyal apostle of the man and the incumbent CM Sampurnanand ensured he would not enjoy the same latitudes or hefty portfolios he once did — this trend continued well into C.B. Gupta’s first government in the state, which was brought about as the result of a convenient alliance between the men. In a note written in 1965 detailing his disagreements and contentions with Gupta, he writes the latter had not paid any heed to his suggestions. He wanted to make space in the cabinet for newer appointees, but Gupta wanted to retain his loyalists. Furthermore, Singh believed he would be best suited for the revenue department given his involvement with the Zamindari Abolition Act, but Gupta put forward Hukum Singh’s name who had been opposed to his more progressive land consolidation measures. Singh’s home and agriculture portfolios had also been highly truncated, and these curbs in his powers were only intimated to him via the media, and not through the government. By removing political pensions and cane development from his portfolio, Singh charged, Gupta wanted to keep patronage in his own hands. He also couldn’t intervene in the 1961 riots where a Hindu mob had burnt down a number of Muslim Houses — where criminal proceedings should’ve been undertaken, none were given Gupta’s quick intervention to rubbish the matter. Gupta evinced a clear bias towards urban mercantile classes and had a complete ignorance of the rural masses. [3] Hence this rivalry cannot be reduced to a petty political tiff but must be historically situated as a part of du jour tensions of caste and urban-rural parity, of which they were both opposing poles. Singh believed that wielding power was important for the public good, since he presented the glaring and dominant chunk of the Indian rural mass that couldn’t make its way to the Parliament and whose energy was being actively suppressed.

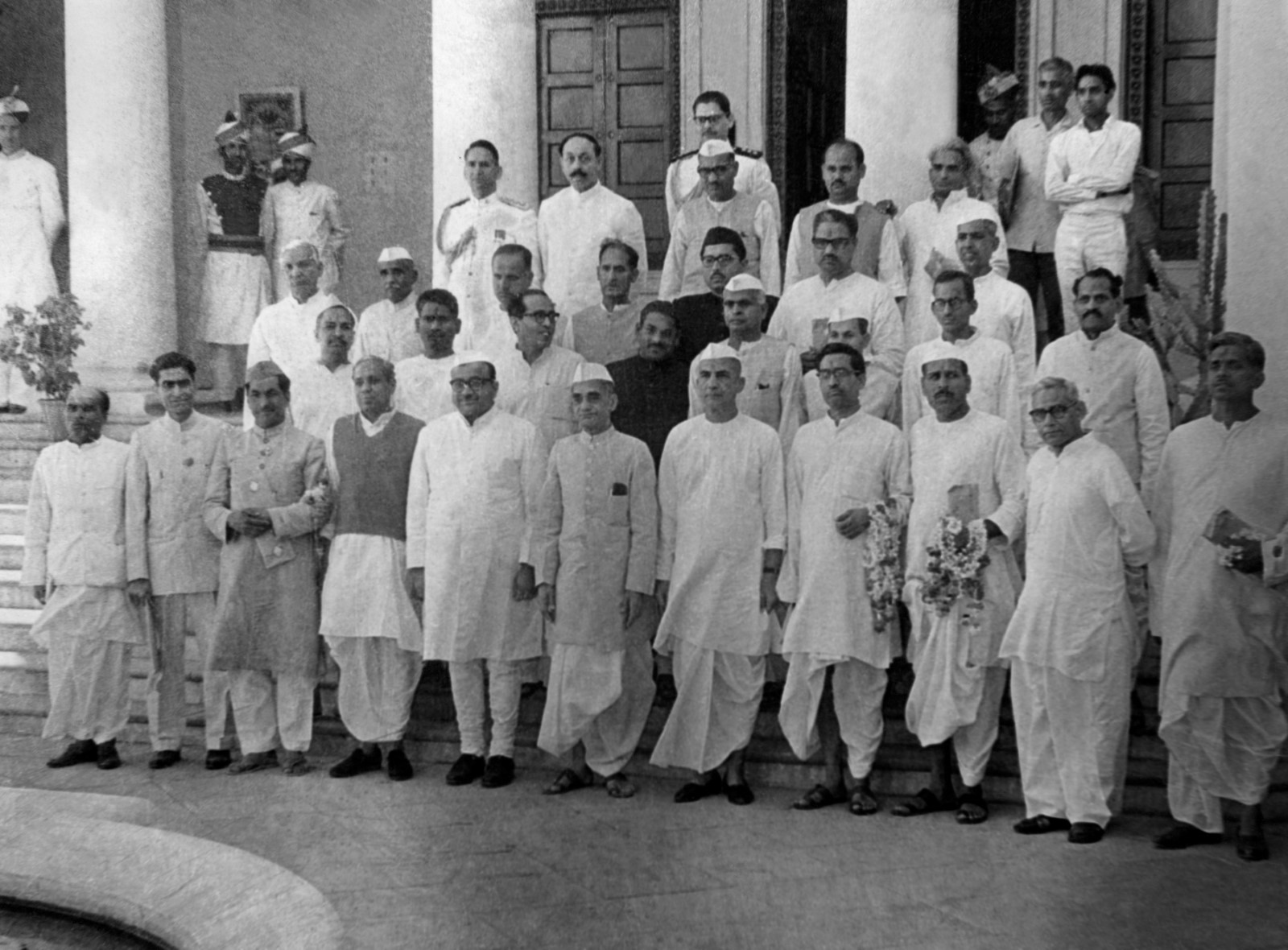

Chaudhary Charan Singh’s Cabinet, April 1967. Highest number of OBC and Dalit Ministers since Independence

Anirudh Pandey in his richly detailed biography, Dhartiputra, has noted that Singh already had offers from the opposition to join them as their Chief Minister, which he refused to take — he wanted to stay on in the Congress. Singh occupied a swing position, where he had at least 50 Congressmen as supporters he could’ve easily taken to the other side and attained a majority — but to Singh the opposition appeared an even more chaotic of melee of interests and ideologies. He believed the Congress to still be the more appropriate fora of effecting change and addressing state-wide issues. To this effect, he threw his hat in the ring to be considered for the position of Chief Minister. Indira Gandhi, who was now PM, sent two of her acolytes to Lucknow to talk him out of this position. What the larger disagreements may have been between them requires more research, but one would have to contend with Jaffrelot’s position [4] that he was often sidelined given his peasant background. The ruling bastion of the Congress reflected the larger hegemonies of the Indian state: urban, upper caste, and unmoored from its overwhelming rural reality [5]. While Brass in the second volume of his biography of Charan Singh notes the Congress decline of the 1960s was a result of “trivial and normal human characteristics” like “human pride, distrust, self-aggrandizement, and self-enrichment” [6], the course of Indian history doesn’t allow us the luxury of such a simple psychologism. These traits were doubtless denouements of the power that mushroomed around upper castes and the latitude they continued to have in national and state politics after Independence. In the 1950s, the Congress party had rejected the Kalekar Report which demanded affirmative action policies for Backward Classes, believing that caste would not survive the country’s ongoing modernisation mechanisms. [7] This obviously did not happen. Congress barely had lower caste representation besides the token, and upper castes continued to hold sway without challenge. This converted into a lack of opportunities for the larger Indian public to gain a real political voice.

To protect the party’s “unity”, Singh acquiesced to withdraw his name on the condition that Ram Murti, Muzaffar Hasan, and Banarsi Das (all close associates of Gupta) be removed from the cabinet due to corruption charges against them. On the face of it, the party leadership agreed. But when the government was formed, portfolios were once again handed to the ministers Singh had protested against. To this, C.B. Gupta replied that the agreement had only been made between Uma Shankar Dikshit and Dinesh Singh [8] who’d been sent by Mrs. Gandhi and he had himself never assented to such a condition. Gupta further refused to entertain any mediation from the centre. [9] Gupta swore in as Chief Minister in March 1967; to an already incensed and isolated cabinet which did not agree with him, and an aggravated opposition that had not been given ample opportunity to present their majority in the parliament. The government fell in a matter of 18 days.

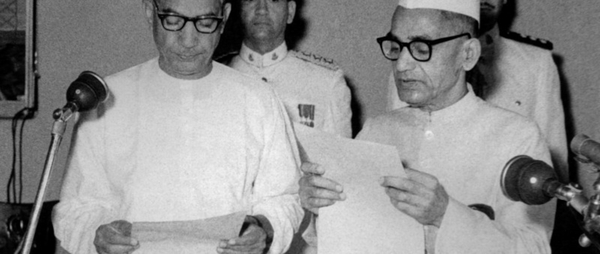

Charan Singh declined to join C.B. Gupta’s government, and the intervening period illustrated the scale of the latter’s bossism in the party. He had absolutely refused to entertain Singh and would publicly make outrageous claims about dissenters. [10] Whatever personal tumult Singh had about leaving the party he had a nearly 40 year association with, were dispelled by this callous attitude. With 17 fellow Congress legislators, Charan Singh crossed the floor of the legislature and took the momentous step of leaving the party. The new party he formed was called Jan Congress (People’s Congress), which now allied with the Samyukt Vidhayak Dal comprised of Jan Sangh, SSP, CPI, Swatantra Party, PSP (and one independent member). He was subsequently was sworn in as the Chief Minister on April 3, 1967 at age 65. M.G. Mathur in his report on the event, engaging in some superlatives, said the occasion was so momentous in the state that people marked as a holy day [11] — the fact of the matter is, Charan Singh after years of being neglected by the Congress had effected for it its own annus horribulis in 1967. A new mass leader had emerged.

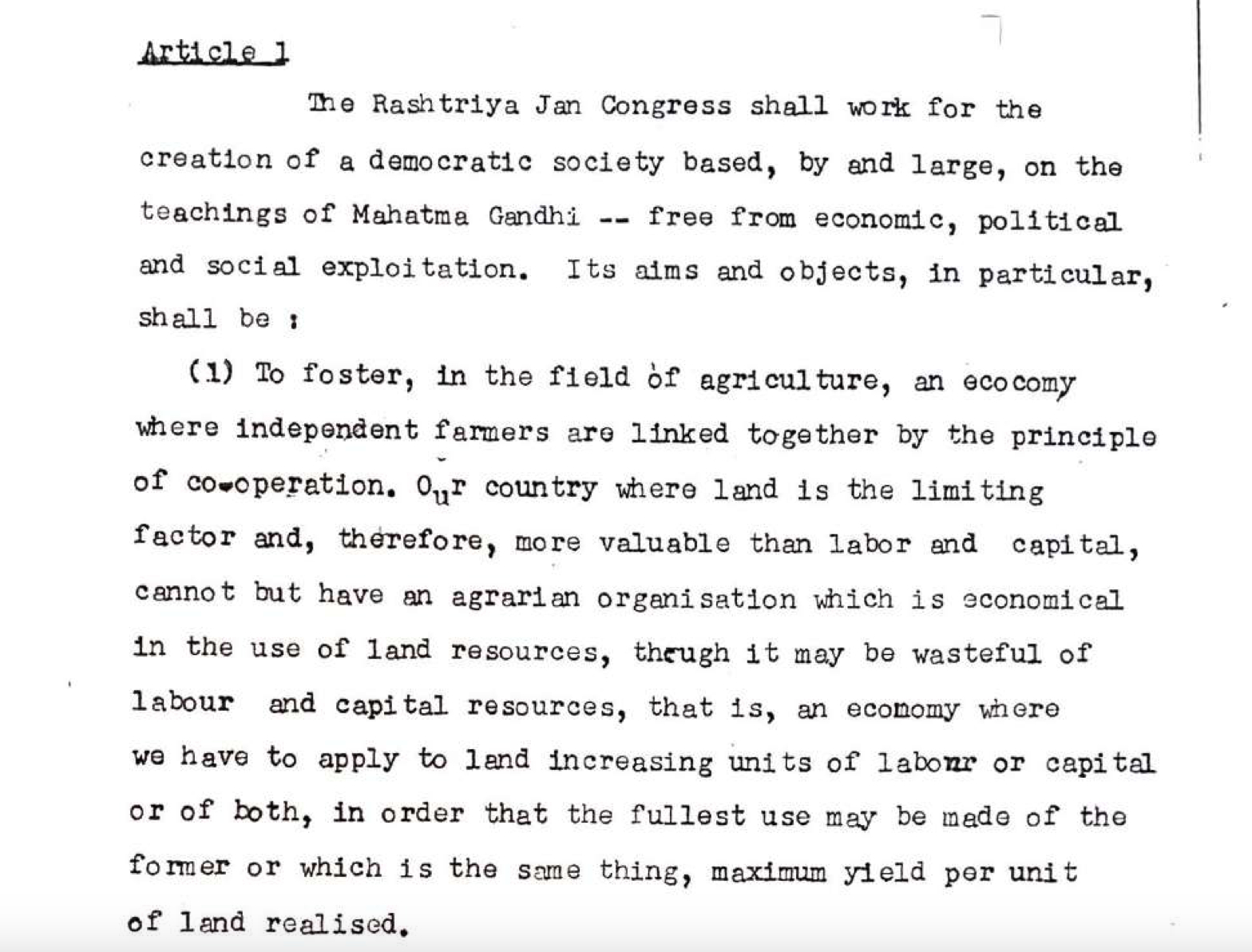

Finally free from Congress’s ideological fetters, Singh was now ready to work out his own political direction. This we see for the first time in the Constitution of the Jan Congress. [12] A rich text, full of incredible insights from his years in politics and engagement with the political economy of Uttar Pradesh, it posed a serious intellectual challenge to the urban and Big Industry skew of the Congress. Singh was not only a political savant but was richly apprised with the latent conflict between the urban and rural space in India — any novelty in politics had to be created bottom up. This struggle, repressed for years, could only emerge in the historical moment of the 1960s when the “Green Revolution” and its attendant technical advancements (high-yielding seed varieties, chemical fertilisers, high machinery) had enriched the peasantry, particularly that of the upper doab in Uttar Pradesh. [13] This group had also ameliorated its political and economic position through a number of structural changes in the government in the preceding years (panchayati raj, for example, removal of tax-farming). The “peasantry” was organizing itself as a distinct political constituent where it couldn’t be neatly grouped as a particular caste and class. The “peasant” emerged as a class unto itself. Singh both seized on this current and gave it momentum (at this juncture he does emphasise “kisaanness” [14] as an identity). This is reflected in the Constitution of his new party: he highlighted the importance of smaller labour-intensive farms, the need for the state to take manufacturing to the rural level and to create a democratic society based on Gandhi’s core principles. Contrary to popular thinking, he did not entirely eschew industry and machinery, but focused instead on employing fully the large population of the country directly in manufacturing on a small scale. Large-scale production needs (Defence, for example) could be supplemented by state-owned manufacturing units. He wanted agriculture to become the motor of industrial development by creating large amounts of surplus self-sufficiently. To him, the village was a higher moral unit than the factory — if India had a germ-cell and humus, it had to be the village. [15]

This text further highlights the importance of a tiered organisation which Singh envisaged on 6 levels going from “Rashtriya” to “kshetriya” as the smallest unit. The “primary” members of the party could not be government beneficiaries in any way — of tenders, controls or licences; had to eschew any and all alcohol consumption and wear Khadi as a rule. These further highlight the importance of Jan Congress in the development of his ideas on political organisation which developed both as a result of his lessons as a Congress members for nearly four decades and his development as an inveterate Gandhian. These ideas are a mix of pragmatism, Gandhianism and a measured political idealism.

In October, 1967, the Jan Congress released its economic policy. [16] A series of succinct vignettes functioned as a broad post-mortem of the Indian economic situation after independence and propounds the Gandhian idea of “trusteeship” as a blueprint for the future. India, as per the party, was neither capitalist nor socialist, but awkwardly dangling in a viscous morass of corruption. The money flushed in the economy by way of deficit financing fell in the wrong hands as black money — the inflation effected for public good was all for nought. The economic policy followed by the Congress government was but a continuation of the colonial obsession with machinery and heavy industry — this had only helped Indian manufacturers and contractors line their pockets while unemployment swelled. Gandhi’s idea of “trusteeship” is put forward as an alternative; wherein possessors of too much wealth become “trustees” for the good of the community. If the rich do not accord of their own will, this additional wealth can be seized from them by way of the state through “minimally violent intervention.” The fledgling party sought to decentralise the means of productions, thwart concentration of wealth, nationalise industries which can’t function on a smaller scale and take Gandhi’s vision of trusteeship on the field.

This manifesto and constitution are sources par excellence to demonstrate Singh’s ability to dovetail his economic exegesis with politics. During the course of these few months where the party sailed through rough waters with a tenuous alliance in the SVD, he managed to flesh out a full vision of how a party was to function. Why is this period then so significant? It shows us that his work with the Bharatiya Kranti Dal, which was to follow, did not emerge in a vacuum. The first few months of his Chief-Ministership were spent moulding a party and its ideology, bespoke to his own interest, almost ex nihilo.

What is perhaps the most significant development of this period is the rise of the backward classes. Charan Singh was the first in UP to understand the importance of these classes and their political potential. A discursive identity came to be formed around the kisan, Charan Singh gave it a fora it had hitherto lacked. When he crossed the floor, he wasn’t defecting, it wasn’t just political ambition, it was history in the making. Out of the 17 legislators that followed him, the majority belonged to lower castes. Nine were what we today call Other Backward Castes (OBCs) and two were Dalits or Harijans then. Under his helm, for the first time in the history of the state, 43 per cent of the ministers and state secretaries were occupied by lower and intermediary castes, compared to the 82% positions occupied by upper castes under C.B. Gupta. [17] This was the real victory, the return of the repressed that became the raison of anti-Congressism.

On November 11, 1967, Charan Singh and non-Congress stalwarts met together in Indore with plans to create a unified national party, which resulted in the creation of the Bharatiya Kranti Dal (BKD). Charan Singh dissolved the Jan Congress and agreed to fight elections as part of the new party. The representing insignia was chosen to be a plough upon a peasant’s shoulder. A singularly evocative image, entirely novel to Indian politics, was also its most ubiquitous — in large swaths and expanses of the country’s villages. This was the novel rise of Charan Singh.

***

This timeline brings together, for the first time, a detailed historical and event-by-event political account of two newly established political parties of the post-Congress era. We have utilised important documents that have not yet been freed from the archives. These would be helpful for any and all students and scholars of Charan Singh, postcolonial India and anyone curious about the state of the peasantry and Indian politics in the 60s and 70s.

Sources and References

.[1] https://charansingh.org/shop/dhartiputra

.[2] Brass, Paul Richard. 2012. An Indian Political Life: Charan Singh and Congress Politics, 1957 to 1967: Regionalism, Discontent, and Decline of the Congress. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB15127549.

.[3] Ibid

.[4] Ganguly, Sumit, Larry Jay Diamond, and Marc F. Plattner. 2007. The State of India’s Democracy. Johns Hopkins University Press eBooks. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA83699378. 69.

.[5] India’s rural population in 1965 was 81 % of the total, and Uttar Pradesh was higher at 85%

.[6] Brass, Paul Richard. 2012. An Indian Political Life: Charan Singh and Congress Politics, 1957 to 1967: Regionalism, Discontent, and Decline of the Congress. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB15127549.

.[7] Ganguly, Sumit, Larry Jay Diamond, and Marc F. Plattner. 2007. The State of India’s Democracy. Johns Hopkins University Press eBooks. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA83699378. 71.

.[8] https://charansingh.org/shop/dhartiputra

.[9] Brass, Paul R. 2014. An Indian Political Life: Charan Singh and Congress Politics, 1967 to 1987. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB19140968. 5.

.[10] https://charansingh.org/shop/dhartiputra

.[11] https://charansingh.org/sites/default/files/Hindustan%20Times%20report%20on%20CCS%20leaving%20Congress%2C%205%20April%2C%201967.pdf

.[12] https://charansingh.org/sites/default/files/Jan%20Congress%20Draft%20Constitution%2C%201967.pdf

.[13] https://www.charansingh.org/sites/default/files/Brass%2C%201980%20The%20Politicization%20of%20the%20Peasantry%20I.pdf

.[14] Jaffrelot, Christophe. 2010. Religion, Caste, and Politics in India. Primus Books.

.[15] Jaffrelot, Christophe. 2010. Religion, Caste, and Politics in India. Primus Books. 436.

.[16] https://charansingh.org/sites/default/files/Jan%20Congress%20Economic%20Policy%2C%201967.pdf

.[17] Jaffrelot, Christophe. 2010. Religion, Caste, and Politics in India. Primus Books. 437.