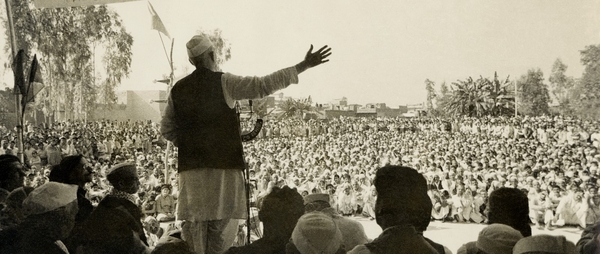

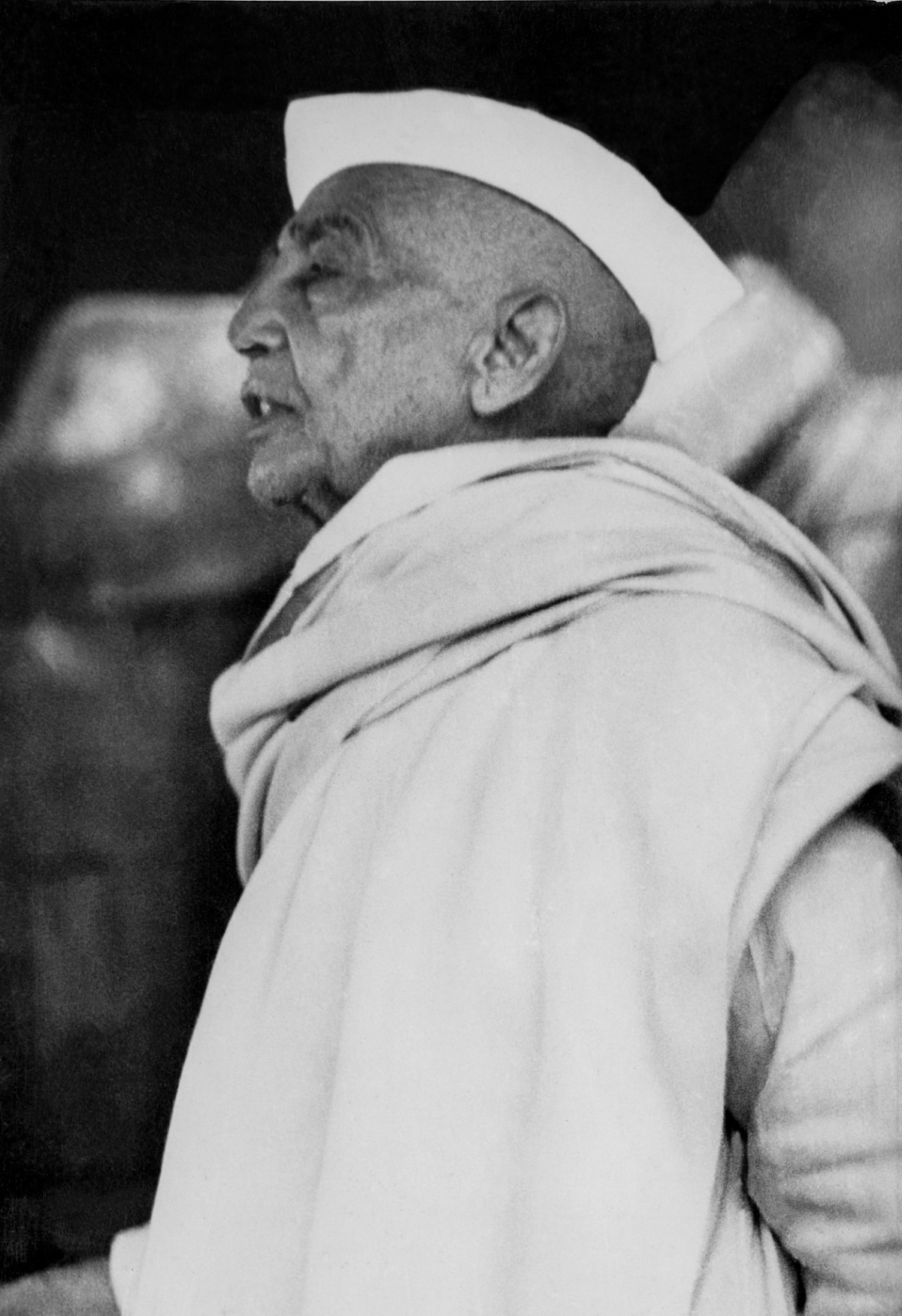

Charan Singh was particularly concerned with the issue of privileged, urban groups wielding power in government services and public life in general.

In the initial decades of his political life, the 1930s, he was primarily concerned with the rural-urban divide and the monopolization of bureaucracy by urban elites. From the 1960s, his focus shifted to caste, specifically incorporating the backward classes (50% of India’s population that holds intermediate status in the caste hierarchy, between the high castes and the Scheduled Castes and Tribes – SC/ST) in the public sphere. His crusade as the principal spokesperson for the aspirations of the backward classes continued as Prime Minister in 1979, when his Cabinet sent a resolution to President Sanjiva Reddy to implement reservations based on caste for Backward Classes (BCs) in Central Services. Though the resolution could not be implemented as he headed a care-taker government, it demonstrated Singh's commitment to justice for the BCs as a matter of long-held belief grounded in the caste-realities of Hindu society. His documented efforts to seek reservations before any other political formation at the Centre pre-dated by a decade Prime Minister V. P. Singh’s implementation of the Mandal Commission recommendations.

Thus, throughout his political life, Charan Singh was concerned with the democratization of public life and ensuring equality of opportunity to all classes of people for competitive exams for government posts as well as in education. This article traces the evolution in his opinions and politics with regards to the issue of representation and, by extension, reservations based on occupation and caste as a form of affirmative action.

Phase One (1936-1967): Reservations for the ‘Sons’ of Cultivators

Singh had voiced similar concerns in a resolution for the Executive Committee of the Congress Party in 1939 [1] which asked the government to guarantee a minimum fifty percent of government employment to ‘tillers of the soil’ so that the peasantry can have its share in government. Again, in another note to the Congress Party Executive in 1947 [2], he sought 60% reservations for ‘agriculturists’ and argued that if the landless labour were also to be included, then the reservation must extend to as much as 75%.

In his March 21, 1947 article [3] on 60% reservation for ‘sons’ of cultivators, Singh was concerned with the ‘step-motherly’ treatment meted out to villagers as the bureaucracy was monopolized by urban elites. Villagers, more than three-fourths of the entire population at that time, were severely under-represented in provincial or central government services. Interestingly, the usage of the word ‘sons’ changes into ‘sons and daughters’ in his later writings (especially those related to the reservation for the backwards classes), stemming from the patriarchal milieu of those times, in which education was regarded as critical for women to better raise children, but their presence in bureaucratic structures was not deemed ideal.

In the article from 1947 [4], he argued that there was an inherent conflict of sympathies and interests between farmers and the urban elite classes, that the urban middle class with formal education looked down upon agriculturists as being only good enough to plough land, and produce food, and as resources to be exploited to cater to the demands of the urban areas. He went on to say that the primary reason for the failure of the Uttar Pradesh Agriculture Department was that it was ‘officered largely by men whose families have had nothing to do with agriculture for generations past, to whom the life of the farmer, in the village, before they entered the Department was virtually a sealed book and who, therefore, make inefficient agriculturists, unimaginative organizers and unsympathetic officers’. ‘There are officers in the Agriculture Department who cannot distinguish between a barley plant and a wheat plant and those in the Canal Department who do not know how many waterings and at what time a certain crop requires’. Singh believed that only those who share psychological and cultural affinities with the cultivator, and are familiar with his economic interests, can contribute substantially to policies meant to uplift the agriculturalists.

Phase Two (1967-1976) – Representation for the Backward Classes

With the formation of the Bharatiya Kranti Dal, Singh was torn between considerations. On one hand, the policy of reservations based on caste could disintegrate the social fabric and further reify fissures on caste lines and affect efficiency. On the other hand, the urban and elite castes (both mostly the same) continued to discriminate against the backward classes in all walks of public life and administration, further strengthening the case for social justice. In an argument very similar to his support for reservations for agriculturalists (that they are better placed to understand the problems faced by the rural populace and farming communities, especially in a country where majority of the population is residing in villages and employed in agriculture), he emphasised that individuals from backward classes (BCs) will have great advantage of possessing first-hand knowledge of the sufferings and problems of the backward sections of society. It must be noted that this change was accompanied with the socialists joining the BKD in the aftermath of Rammanohar Lohia’s death in late 1967.

In an interview, Indira Gandhi had said that it was only after Charan Singh became a part of the Union government that caste became important in national life. In his sharp rebuttal to her charge, Singh wrote, “… to put it moderately, this is nothing but a deliberate misstatement meant to defame me, and, thus, divert people’s attention from the misdeeds and failures of her government”. He challenged her to point out even a single such decision taken by him that might be seen to accentuate caste feelings. He further pointed out that even a cursory glance at the list of her Cabinet as well as the candidates she selected for the UP Assembly proves that the allegations of being a casteist rather fit her very well. Interestingly, Singh always pointed out the disproportionate presence of the upper castes in the political and administrative offices at the highest level. The representation of SC, ST and OBC employees in Class I public employment was much smaller to their proportion of the total population.

In his three volumes on the life of Chaudhary Charan Singh, eminent political theorist Paul R Brass has also noted "... Singh would now and then recite figures showing that 45% of particular govt services were dominated by Brahmins, Baniyas, Khatris and elite castes generally, whereas the backward castes had negligible representation, amounting to less than 1% in some departments. He would point out that Harijans, because of the reservations accorded to them in govt services since independence, were far better represented than the BCs’. During the period of Janata rule between 1977 and 1979, at the centre and in the states of northern India, Singh supported reservation policies for BCs as adopted by the Janata party governments of Uttar Pradesh led by Chief Minister Ram Naresh Yadav and Bihar Chief Minister Karpoori Thakur. However, he did not argue for proportionate representation of positions for BCs, but thought that the reservation policy of 15% for recruitment of BCs adopted by the UP govt was reasonable (Brass, 2011, pp. 11). As always, Charan Singh balanced social equity the need for administrative efficiency.

A brochure published by the Bharatiya Kranti Dal (BKD) titled Aims and Principles of Bharatiya Kranti Dal [5], which served as BKD Election Manifesto for General Elections to the Legislative Assembly in Uttar Pradesh in 1974, also contained a clause for backward classes reservations. It concluded that there is no way out but that a share in Government jobs, say, 25 percent, be reserved for young ‘men’ coming from these classes, as recommended by the Backward Classes Commission appointed in 1955 under the presidentship of Kaka Kalekar by the Union Government itself, under Article 340 of the Constitution. While the commission had recommended reservation of 25% in Class A, 33.3% in Class B and 40% reservation in Class C and D services, Singh stopped short at 25% for all services.

Interestingly, in a manuscript on the ‘facts and fallacies of Lok Dal in Bihar’ [6], Singh had also noted that the greatest drawback of socialists was their lack of cohesive action when the opportunity of action descended. He felt that if left to them, the Mandal Commission will become a mere tool of propaganda.

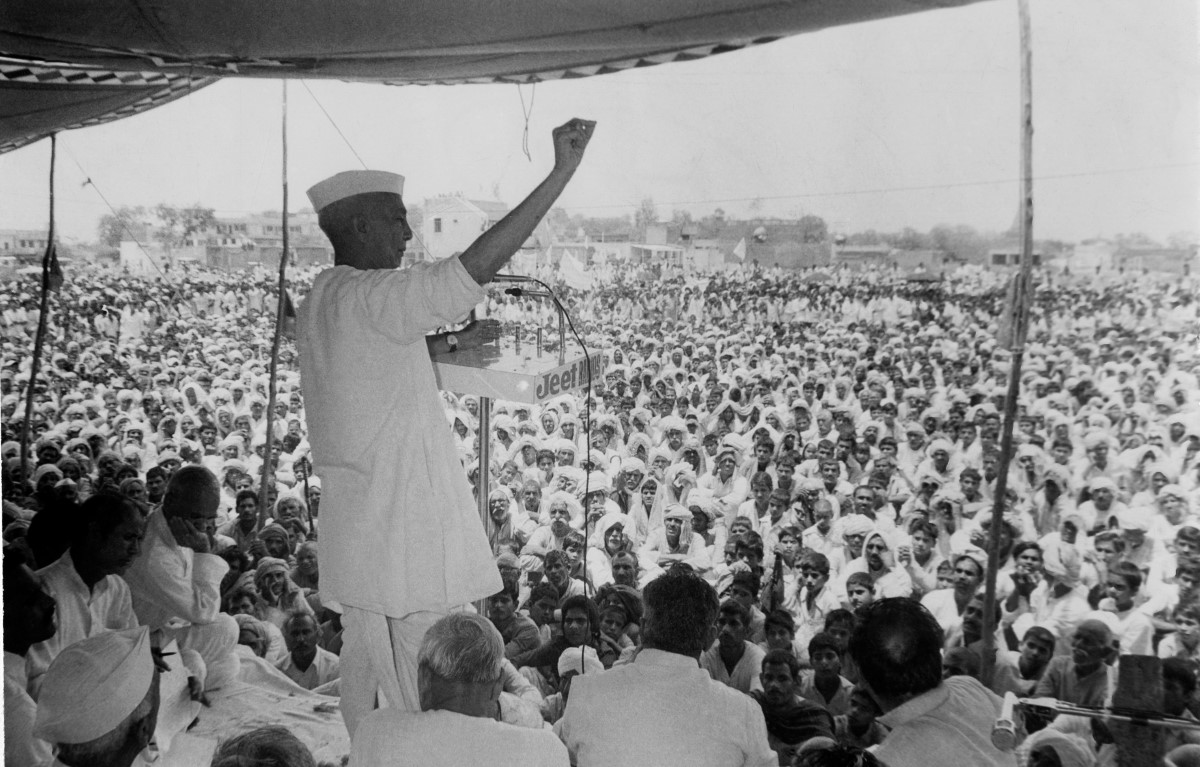

Phase Three (1977 onwards): in the Central cabinet

After the breakup of the Janata government, Charan Singh became the fifth Prime Minister of India on 28 July 1979 as head of a short-lived coalition. In the short period, he took concrete measures to bring about reservations for the BCs. Singh’s letters to the Deputy Prime Minister YB Chavan and SN Kacker, then Minister of Law, Justice and Company Affairs, both dated 3 December 19791 talk about the proposal for 25% reservation for backward classes in central class I and II services to be immediately taken up in the cabinet meeting the other day. Singh also firmly believed that children of government officers should be ineligible for selection for government posts. In another letter to the Deputy PM dated 6 December 1979 [7], Singh said that ‘sons and daughters of those members of scheduled castes and tribes and backward communities who had themselves secured jobs by taking advantage of the reservation clause or are assessed to income tax will not be allowed to take advantage of reservations’. A cabinet note dated 6 December noted that the socially and educationally backward classes other than the SCs and STs, both Hindus and Muslims, constitute more than 50% of the entire population and find hardly any place in the administration. While reservations cannot be a permanent feature of the polity, in an unequal social order like the one that currently exists, there is in fact no alternative to the policy of preferential opportunities.

It was reported that a few weeks before the 1980 elections, the coalition government headed by Charan Singh proposed to reserve 25% central government jobs for Backward Classes. The proposal was dropped after the President objected that it violated an agreement that the caretaker government would refrain from taking policy decisions which might amount to electoral initiatives [8].

Reservations for BCs and SCs/STs formed a key component of Lok Dal manifesto in 1980 and 1984 as well as Singh’s addresses at annual party conventions. In a statement titled On Social Policy and Reservation adopted by the National Executive of the Lok Dal at its meeting held in New Delhi from 10-12 April 1981 [9], the Lok Dal suggested ‘an expanded system of reservation in services in terms of four broad categories’. Each category was to get representation in services proportionate to their population. The first category was to consist of the Schedules Castes and Scheduled Tribes who already enjoyed constitutional protection. Their reservation must be continued. All backward communities, irrespective of their religions, were placed in the second category. Their share was to be proportionate to their population share. The third category consisted of the kisan communities (excluding those falling in the fourth category). Their presence also must be in accordance to their population. The last category consisted of the upper castes and some advanced sections belonging to minorities. Since they were over represented in the services, their share must be limited to their strength in the total population.

The resolution adopted by Lok Dal on 7/8 March 1981 at Nasik [10] also advocated for reservation of 25-30% for backward classes. To ensure that the proposal was not bypassed in the name of ‘merit’, the resolution also suggested that there should be competition and merit test ‘only within the category and not between different categories’.

Madhu Limaye, the General Secretary of Lok Dal argued for a fifth category of reservations for those who opted for inter-caste marriages. In his article ‘Impact of Reservation Policy’, Limaye argued that the real causes of mounting social tensions were pressure of increasing population, stagnation of economy and resultant failure of employment opportunities to expand proportionately, and that the purpose of reservation was not to solve these economic problems [11]. Its purpose was to give the depressed sections a stake in the state, and a feeling of power and equal rights.

Conclusion

Thus, over the course of six decades, the politics and policies of Singh and the political parties he founded came to embody a comprehensive legislative and administrative approach to representation for the social disadvantaged. This approach included a spectrum of social groups, encompassing agriculturalists, Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Classes, while limiting the representation of the over-represented upper castes.

Sources and References

.[1] Resolutions for the Executive Committee by Charan Singh dated 5 April 1939, accessed in File 2, I Instalment of Chaudhary Charan Singh papers at PMML https://www.charansingh.org/archives/chaudhary-charan-singh-reservations

.[2] Document accessed in File 163, II Instalment of Chaudhary Charan Singh papers at PMML

.[3] Singh, Charan (1947). “Why 60 percent services should be reserved for the sons of cultivators”. 21 March 1947. https://charansingh.org/archives/why-60-government-services-should-be-reserved-sons-cultivators

.[4] Ibid https://charansingh.org/archives/why-60-government-services-should-be-reserved-sons-cultivators

.[5] Aims and Principles of Bharatiya Lok Dal’ printed by Vikas Printing Press, Lucknow in January, 1971 https://charansingh.org/archives/bkd-aims-and-principles

.[6] Document from 1980 titled ‘The facts and fallacies of Lok Dal in Bihar’ by Prof. Prabhas Chandra. Accessed in the Second Installment (File 163) of Chaudhary Charan Singh files at PMML. https://charansingh.org/archives/facts-and-fallacies-lok-dal-bihar

.[7] Letters dated 3-5 December 1979 accessed in File 167, II Instalment of Chaudhary Charan Singh files at PMML https://www.charansingh.org/archives/letters-exchanged-pm-bc-reservations

.[8] Undated Note on BC reservations accessed in File 167, II Instalment of Chaudhary Charan Singh files at PMML https://charansingh.org/archives/undated-note-reservation-bcs

.[9] The statement titled ‘On Social Policy and Reservation’ dated 12 April 1981 accessed in File 179, II Instalment of Chaudhary Charan Singh files at PMML https://www.charansingh.org/archives/statement-adopted-lok-dal

.[10] Resolution dated 7-8 March 1981 adopted by the Lok Dal in Nasik accessed in File 176, II Instalment of Chaudhary Charan Singh files at PMML

.[11] ‘Impact of reservation policy’ by Madhu Limaye from May 1985 accessed in File 176, II Instalment of Chaudhary Charan Singh files at PMML

[12] 1979 December Note on Reservations by Secretary to Prime Minister Charan Singh https://charansingh.org/archives/note-reservations-secretary-prime-minister-charan-singh