१९६० के दशक के उत्तरार्ध में भारत में दो राजनीतिक तूफ़ान आए: भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस के टूटने की शुरुआत, और देश के सामाजिक रूप से कमज़ोर वर्गों में राजनीतिक चेतना का उभार। ये दोनों आने वाले दशकों में सामाजिक-राजनीतिक विकास को गति देने वाले थे।

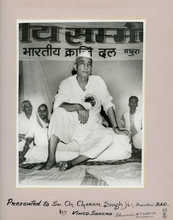

भारतीय क्रांति दल (बीकेडी), इन शक्तिशाली जुड़वां ताकतों का एक मिश्रण, राजनीति को बदलने और यूपी की राजनीति में एक तीसरा स्थान बनाने आया, जिसे कांग्रेस के प्रभुत्व ने दबा दिया था। १९६७ में गैर-कांग्रेसी विचारकों के एक समूह द्वारा स्थापित, इसने खुद को किसानों की पार्टी के रूप में स्थापित किया, और “किसान” के इर्द-गिर्द एक राजनीतिक पहचान बनाई, जो आज भी भारतीय राजनीति में गूंजती है। इस कदम ने इसे कांग्रेस के पूंजीवादी, जमींदार समर्थक एजेंडे से पूरी तरह अलग जनादेश दिया, भले ही इसके विपरीत बयानबाजी क्यों न हो। इसी समय, चरण सिंह के नेतृत्व में, बीकेडी ऐसे गठबंधनों और गठबंधनों का दलाल बन गया जो वैचारिक सीमाओं से परे थे। भारत में ऐसा प्रयोग पहले कभी नहीं देखा गया था। इन उपलब्धियों के बावजूद, पार्टी स्वतंत्र भारत की राजनीतिक अर्थव्यवस्था में अपेक्षाकृत गुमनामी में चली गई है।

निम्नलिखित समयरेखा में, हम पार्टी के इतिहास, इसके विकास के चरणों और भारतीय राजनीति में इसके विकास को एक साथ जोड़ते हैं, जिसे यह एक साथ आकार दे रही थी। हम बीकेडी को क्षेत्रवाद के आरोप से बचाते हैं - इसका दृष्टिकोण हमेशा अखिल भारतीय, राष्ट्रवादी और गांधीवादी था - और यूपी में जाति और वर्ग का तिरछापन था। हम समझदार पाठकों के ध्यान में तीन स्पष्ट रुझान लाते हैं जिनके माध्यम से बीकेडी और चरण सिंह विकसित हुए: कांग्रेस के साथ शुरुआती दूरी और तनाव, ग्रामीण और कृषि एजेंडे पर आधारित एक नई पार्टी की दृष्टि, संयुक्त विधायक दल के रूप में गठबंधन बनाने के शुरुआती अनुभव और अंत में एक ऐसी पार्टी का निर्माण जिसके आधार पर इन एजेंडों को साकार किया जा सके।

पहला चरण १९६७-१९६८ है, जो उत्तर प्रदेश के मुख्यमंत्री के रूप में चरण सिंह के इस्तीफे और एसवीडी के पतन के साथ समाप्त होता है। दूसरा चरण १९६८-६९ है जहाँ चरण सिंह क्षेत्रीय इकाइयों के गठबंधन से परे पार्टी को विकसित करने के लिए कड़ी मेहनत करते हैं। इस अवधि में राष्ट्रीय पार्टी के निर्माण में नए प्रयोग हुए क्योंकि सिंह ने बीकेडी की आंतरिक संरचना और सैद्धांतिक रेखाओं पर विचार किया और साथ ही गैर-कांग्रेसी दलों के व्यापक आधार वाले विलय की कल्पना की और कांग्रेस के विपक्ष के लिए वोटों के विखंडन को मजबूत किया। एसवीडी जैसे नाजुक और अस्थिर गठबंधन की भट्टी में इन विचारों को गढ़ते हुए, वह भारत में बहुदलीय शासन के विचार के प्रति उदासीन हो गए थे। बीकेडी ने इस अवधि में कई दलों के साथ विलय करने की कोशिश की, लेकिन बहुत कम प्रभाव पड़ा। इन प्रयासों का अभी भी उनके राजनीतिक विचारों और अलग-अलग समूहों को एक झंडे के नीचे लाने की क्षमता पर स्थायी प्रभाव है।

बीकेडी का तीसरा और सबसे महत्वपूर्ण चरण 1969 में कांग्रेस के विभाजन, इंदिरा गांधी के पूर्ण प्रभुत्व की शुरुआत, कांग्रेस की उत्तर प्रदेश राज्य इकाई की स्वायत्तता का उनके सत्ता में आना और कमलापति त्रिपाठी के कार्यकाल से शुरू होता है। बाद में जातिवाद, भ्रष्टाचार और अल्पसंख्यक विरोधी हिंसा का दौर आया, जिसने बीकेडी को अनुसूचित जातियों और मुसलमानों तक अपने जनादेश को काफी हद तक बढ़ाने की अनुमति दी। इसने पार्टी और सिंह को एक वास्तविक जनाधार दिया और इसे दो युद्धरत कांग्रेस गुटों के लिए एक व्यवहार्य विकल्प के रूप में प्रस्तुत किया। यह चरण 1974 में भारतीय लोक दल के निर्माण के लिए कई दलों के विलय के साथ समाप्त होता है। इन चरणों में उल्लेखनीय बात उनकी अडिग सिद्धांतवादी राजनीति है, जिससे वे राजनीतिक हवाओं की दिशा के बावजूद अडिग रहे। इस अवधि में सिंह ने घोषणापत्र लेखन की कला में भी महारत हासिल की, जहाँ उन्होंने अपनी बुद्धि और भारतीय राजनीतिक अर्थव्यवस्था में गहरी रुचि के फल का उपयोग किया और साथ ही इन परिष्कृत विचारों को सरल बनाकर उन्हें बड़े पैमाने पर अशिक्षित दर्शकों तक पहुँचाया। ये घोषणापत्र एक आत्मविश्वासपूर्ण और स्पष्ट राजनीतिक आवाज़ को दर्शाते हैं, जो नेहरू और इंदिरा गांधी के सत्ता में रहने के कार्यकाल की आलोचना और भविष्य के लिए एक व्यावहारिक दृष्टिकोण के रूप में कार्य करते हैं, जो १९७७ में जनता पार्टी के राजनीतिक दृष्टिकोण में परिणत होगा।

यहाँ उपलब्ध कराए गए दस्तावेज़ उत्तर प्रदेश में इस महत्वपूर्ण चरण का एक सार्वजनिक संग्रह बनाते हैं, जो एक ऐतिहासिक व्यक्ति के दृष्टिकोण को प्रस्तुत करते हैं, जिनके शब्द आज शायद ही कभी सुने जाते हैं। इन दस्तावेजों को फाइलिंग कैबिनेट में कैद से मुक्त किए बिना किसी भी सार्वजनिक अभिलेखागार का काम पूरा नहीं होगा। उन्हें व्यापक पाठक वर्ग तक पहुंचाना चरण सिंह अभिलेखागार का सबसे बड़ा उद्देश्य है।

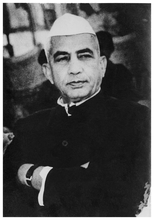

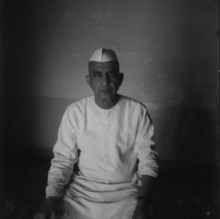

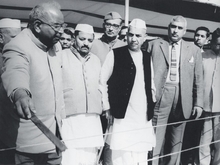

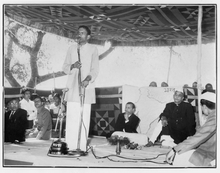

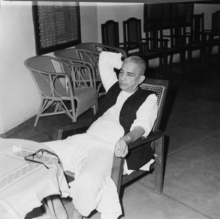

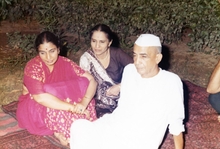

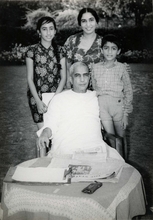

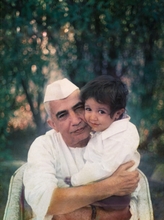

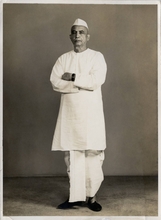

इस समयरेखा में परिवार के अपने संग्रह से पहले कभी न देखी गई तस्वीरें भी शामिल हैं।